Overcrowded islands are going to downgrade the tourist experience.

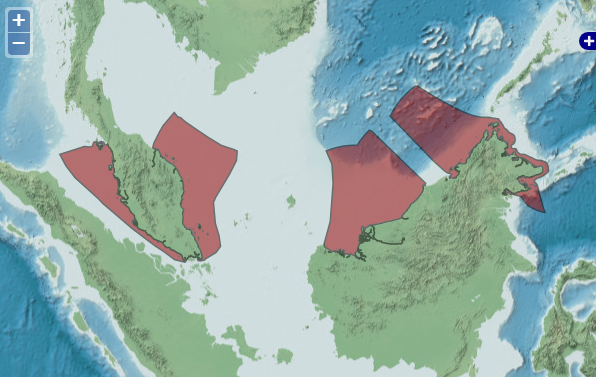

First it was Tioman and the proposal for a new airport. Then there were rumblings about extending the airport at Redang…then we heard about two new resorts at Perhentian Island…and the latest – a proposal for a seaplane facility on Perhentian.

What on earth is going on?

In case I really need to say it again: RCM has never been against development.

We understand that tourism is an important part of the economy. We understand that tourism is important for jobs, particularly local communities in remote areas.

But this upsurge in development proposals post-covid is becoming a concern. I have written separately about my recent experience on Tioman, seeing so many tourists arriving in a small village. If nothing else, the islands are becoming overcrowded; that’s going to downgrade the tourist’s experience. And maybe they won’t come back – and worse, there’s a risk they will tell others of their poor experience.

Picture of overcrowded jetty taken by our team on Tioman island.

And what about that promise of jobs for islanders?

One resort I visited has restaurants, shops, bars, and water sports…tourists don’t need to leave the resort to find these services - which the villagers used to provide. Now, they are being provided in-house. Often by staff brought in from outside.

The locals are now either jobless or having to work for those big resorts…no longer their own bosses, no longer running a family enterprise, no longer in control.

Someone else has come to their island and displaced them.

If Malaysia wants to be a mass-market destination, so be it.

If that is the decision, we respect that. But a decision like that should be very deliberate, it should be carefully thought out – not an accident caused by a lack of controls over resort development and growing tourist numbers.

Are over-crowded beaches and tourism sites what we want?

MOTAC and Tourism Malaysia might be pleased to see increasing visitor numbers. But are the islanders? Are the local communities? And what about the impact of all those visitors on ecosystems?

Covid provided an opportunity to take another look at tourism, and to ask ourselves: “Who is tourism for?”

It is looking increasingly like it isn’t for local communities who find themselves besieged by huge numbers of tourists. As the islanders on Tioman told us during our consultations on the proposed airport – “enough is enough”.

Is this the direction in which Malaysia wants its tourism to go?

Over-crowded beaches and tourism sites, more and more resort development (“container resorts”, I kid you not – resorts built out of old shipping containers), local islanders left behind by full-service resorts?

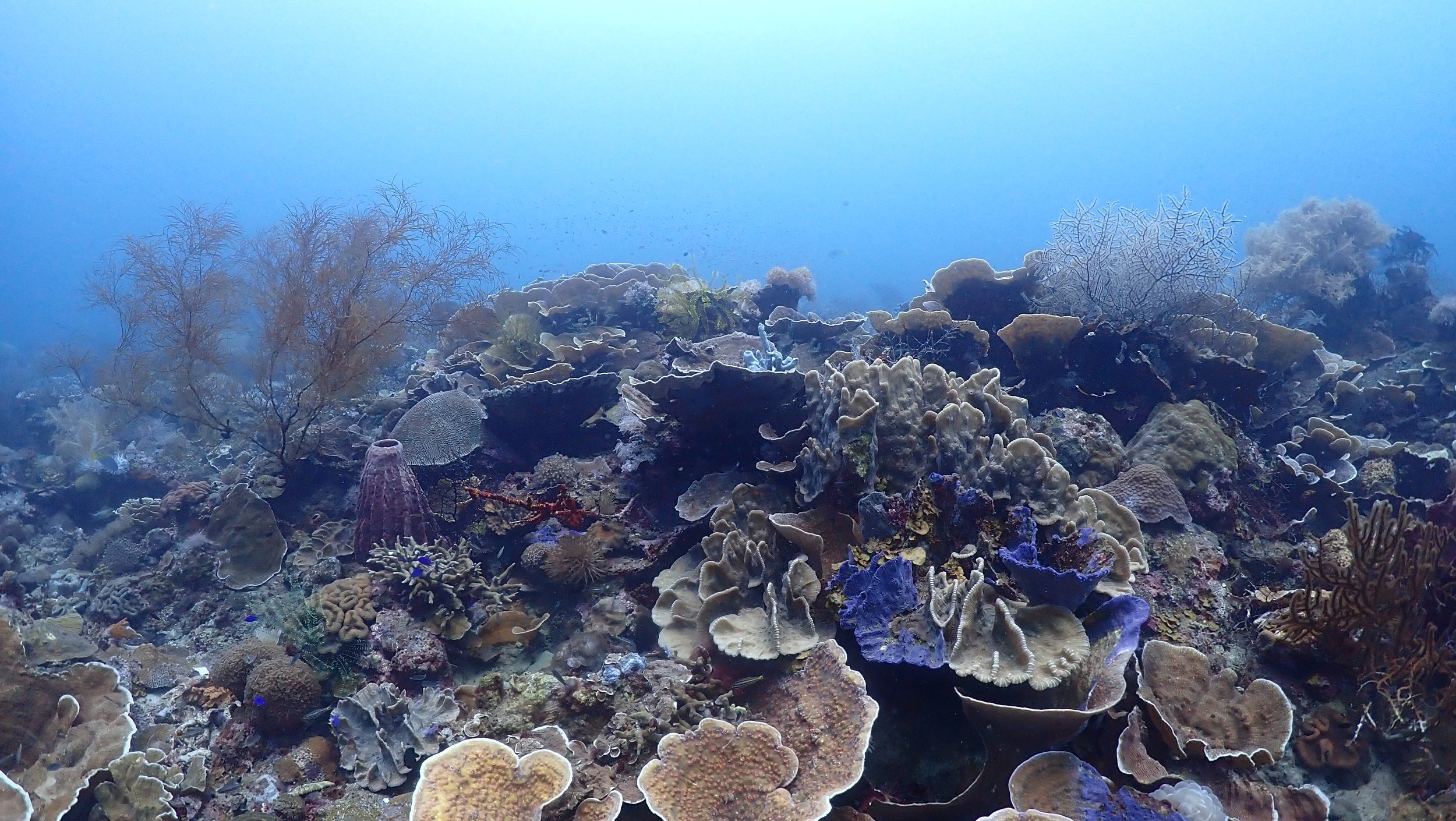

Or should we re-visit that post-covid conversation and explore other opportunities – lower volume, higher value tourism that looks for pristine, quiet, peaceful, authentic experiences – which, I have said before, we have plenty of...for now.